Marlene On the Wall

Trailing in the shadows of a Hollywood icon and a global sensation.

“Marlene watches from the wall,

Her mocking smile says it all,

As she records the rise and fall

of every soldier passing.”—from the song Marlene on the Wall by Suzanne Vega

Growing up in the 1960’s in a closed adoption, I used to imagine that I was the “love child” of Marlene Dietrich and some handsome Hollywood leading man, and that secretly, she was my biological mother.

Of course, Marlene would have been nearly 60 years old when she had me, but I was very good at inventing near plausible backstories and then inhabiting that drummed up fiction in my mind as though it were wholly possible. And while I had numerous make-believe mothers: Maria Callas, Judy Holiday, Marilyn Monroe, and Doris Day to name but a few, I would always come back to the world’s last goddess, the blue angel herself, Marlene!

On Saturday mornings, instead of watching all the cartoon channels, I would be up extra early to take in the old reruns of classic movies. Along with Shirley Temple, Warner Oland (as detective Charlie Chan), Laurel and Hardy, Deanna Durbin, Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, I discovered half a dozen Marlene Dietrich movies that mesmerized me from start to finish.

In the classic film Morocco, Marlene’s American movie debut, she plays the world weary Mademoiselle Amy Jolly, a chanteuse who headlines a small nightclub in the city of Mogador. A love triangle quickly ensues between Amy, a dashing French legionnaire, and a wealthy philanthropist. The film is best remembered for Marlene’s portrayal of a disillusioned, heart-on-her sleeve saloon singer, and the screenplay includes Dietrich's heart-stopping, pre-code, "gender-fluid performance" where she is dressed in top hat and tails and seduces a young female cabaret patron with an overzealous kiss.

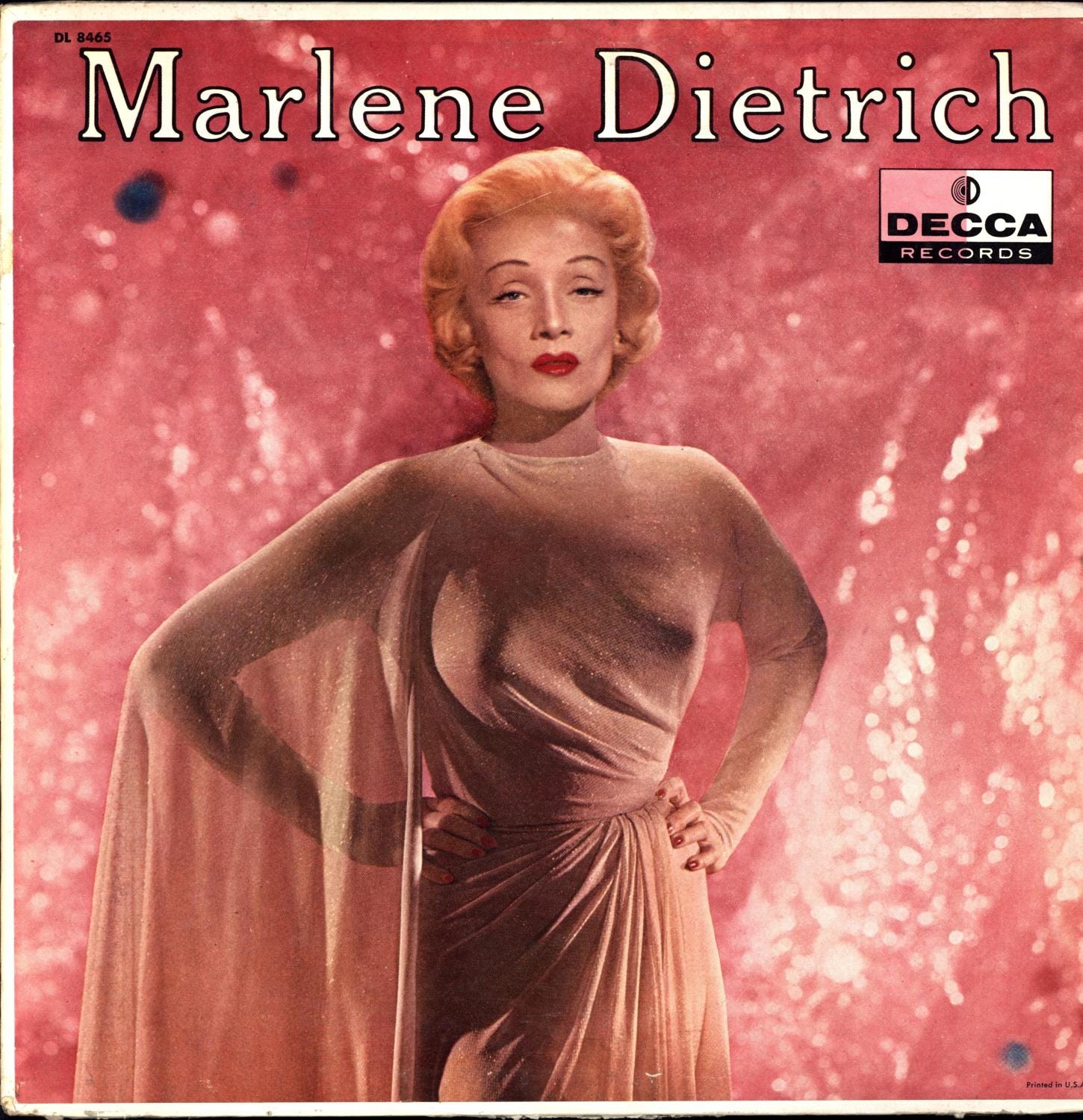

Somewhere in our extensive family vinyl collection from the psychedelic seventies, lodged between the greatest hits of Gertrude Lawrence, the soundtrack to the Broadway version of Hair, and the ukulele tunes highlighting the album, Waikiki Hawaiian Strings, there is a scratched, but playable Decca studio recording of Marlene’s most memorable songs: Cole Porter’s You Do Something To Me, Marlene’s own signature song, Lili Marlene, and the unforgettable Boys in the Backroom written by Frederick Hollander.

These songs would later become standards in Marlene’s cabaret shows that she would perform around the world in her later years. But there I was, singing every memorized word of that album out loud at twelve years old, as I rode my Schwinn Sting-Ray bicycle to Catholic grade school, complete with its leopard print seat and yellow and black streamers that blew in the wind from the extended handlebars. Even with a replica, 1930’s silver cigarette holder glued onto my bike basket, no one would ever guess how deeply obsessed I was with this legendary movie star.

Except, ironically perhaps, my own adopted mother.

Known for her savvy bargain hunting at local estate sales, my mom came upon a set of classic silver-rimmed, art deco champagne glasses that had been certified as once belonging to the legendary Marlene Dietrich herself. I was getting my first off-campus apartment in college at the time, and suddenly found myself serving bargain boxed wine from these incredibly elegant champagne flutes—the kind of stylish glassware you’d see in a Hollywood Busby Berkley musical.

I have treasured these delicate crystal cups for decades, until I decided just recently, to hand them down to beloved friends. I’ve long since lost the paper certificate that authenticated the glasses as former property belonging to the Blonde Venus herself, but they hold great sentimental value for me—and I’m certain my extended family appreciates having these priceless heirlooms.

Like so many before me, scores of fans gravitated to Marlene’s public image because it seemed to openly defy the sexual norms and mores of the day—she was known for her androgynous film roles and her rumored off-camera bisexuality (Greta Garbo and Edith Piaf, were but two of her supposed secret lovers.)

When I lived and worked as an English teacher in Paris in the early 1990s, I attempted to follow a path to several of the superstar’s haunts. I discovered that while living in Paris, Dietrich reportedly had an affair with Suzanne Baulé, also known as Frede, a cabaret hostess whom she met at Le Monocle, a women's nightclub on Boulevard Edgar-Quinet in Paris.

I made a pilgrimage to visit this iconic Parisian lesbian bar one afternoon when I was finished teaching English idioms to business professionals. The name of the club comes from the fact that the monocle was used as a symbol of recognition among lesbian individuals in the early 20th century. After the "flamboyant 1920s and the retrenchment of the 1930s, the infamous bar was not surprisingly closed during the occupation of France by Germany during the Second World War.

In Marlene’s hey day, Le Monocle was one of the first well-known lesbian clubs in the city. At its peak, the speakeasy was considered a luxurious club where "fashionable" women could dance, talk, and kiss without fearing judgment or persecution. Regarded as a popular venue for Sapphic lovers in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s, its reputation as a safe zone for women was no secret.

I remember so well taking the metro up to Montparnasse, a rather dodgy part of the 14th arrondissement, and standing outside the busted door of 60 Edgar-Quinet. I peered inside the window that framed the dusty and decrepit lounge room—flaking paint and spotted walls, the decaying tavern had clearly seen better and brighter days. But standing there for a moment, I could imagine a glowing Marlene seated at the bar with a bevy of young paramours gathered around her.

I’m certain that just a glint of a smile from her lips back then would have been enough to send anyone into an unforgettable head-spin.

She lived as a recluse in her later years, nearly forgotten except for her enduring performances in Orson Welles’ masterpiece movie, Touch of Evil and in Billy Wilder’s monumental film, Judgment At Nuremberg. And of course, her timeless music recordings have never faded.

I would often walk around 12 Avenue Montaigne in Paris where she spent the final thirteen years of her life, mostly bedridden, allowing only a select few—including family and employees—to enter the apartment. I would pace the sidewalk across the street from the modern apartment building and imagine the pungent loneliness she must have experienced, a prisoner to her aging body and to her once stellar public life.

(The redone piano lounge of the Hotel de Crillion, a notable haunt of Marlene’s back in her starlet days.)

I lived in Paris for two years and just before I left to go back to the United States to take on a serious teaching career at a university in Chicago, my life took a dramatic leap towards channeling the ghost of Marlene.

Back then, I lived on the Rue de Casablanca in the 15th arrondissement with my dear friend Abra, and every now and then her flamboyant friend Stacy would come over to tune her piano and sing a few show tunes with us in the apartment. We’d gather around the antique ivories, and sing a few choruses of “The Trolley Song” from Meet Me in Saint Louis or “If I Loved You,” a heart-wrenching ballad from the musical Carousal.

One afternoon, Stacy invited Abra and I to his closing piano performance at the posh Hotel de Crillion in the distinguished eighth arrondissement near the Tuileries Garden and the Champs-Elysées. Abra and I found ourselves that same evening in a soft tufted banquette in the swanky cocktail bar of the hotel, listening to Stacy sing show-tunes in English to the quietly reserved crowd. Though the space we were seated in had been refurbished, it was still the same chic lounge spot where Marlene was often spotted, sipping her chilled champagne cocktails in the late 1930s before retiring to one of the hotel’s luxurious chambers.

That evening, Stacy invited both Abra and I to sing in the background of his rendition of the song, “The Impossible Dream.” We leapt at the chance to have our moment to sing to the elegantly boozy sophisticates. The extended applause afterwards gave Stacy a moment to consider that both of us should take a moment to sing a solo number. Abra blushed, and because she was often so forgetful at remembering lyrics, she handed the microphone to me.

“Do you know the song from Marlene’s film The Blue Angel?” I shyly asked Stacy.

“You mean the one about the moths and their singed wings?” he responded wryly.

The room seemed to morph into flickering candlelight and it was just me with a slight tremble in my voice as I moved the microphone up to my quaking lips and slowly began to sing the lyrics, “Falling in love again, never wanted to, what am I to do, I can’t help it.”

It never fades from my memory—that quiet vintage apartment on the Rue de Casablanca, back in the early nineties, with Marlene on the wall—and all my urgent, youthful desire to get behind the seductive Snow Queen’s half-smile, to be a part of her elegant entourage, to travel in her quick footsteps, her French beret tilted just so, grasping for that thin trail of her cigarette smoke that somehow always leads back to the piano bar at the glamorous Hotel de Crillion, and to blamelessly, guiltlessly, hopelessly, fall in love all over again—yes, that is Marlene’s undying, irresistible spell.

Fall under it with me.

Resources

People’s World has a fascinating article on Marlene Dietrich and her pro-American, anti-Hitler, anti-fascist worldview.

If you’re visiting Paris and you want to get entangled with Marlene’s timeless ghost, visit the gorgeously refurbished piano bar at the Hotel de Crillon —hotel rooms there start at around two-thousand euros a night! Lili Marlene!

(All photos by Gerard Wozek or in alignment with Creative Commons.)

Hi Gerry,

Your essay mesmerized me. Delving into your memories of Marlene Dietrich must have felt so good. Before this post, I knew very little about her, and she does, indeed, sound fascinating. And imagining you at her haunts was wonderful.

I'm also impressed that you taught English in France for two years. What an incredible immersive experience! Singing around the piano with your friends sounds magnificent.

You know who else is kind of androgynous? Barbra Streisand. In her 900+ page memoir (all the pages were fascinating) she discusses from time to time how she liked to encompass the female and male part of her through her vintage wardrobe.

I think it's also amazing that you fantasized about Marlene and others as being your birth mother. Adoption is a complex issue, as you well know, and I think about my adopted daughter. Does she, too, fantasize others as being her birth mom?

Thank you for a wonderful read. Excellent job!

Bien fait, Gerry, and Vive Marlene! You've made us fall under her spell along with you! Merci.